Amongst the abounding number of sub-genres of noir (hard-boiled, grip-lit, psychological suspense, urban noir, existential noir, tech noir, neo-noir, domestic noir…too many to list here) there has been, within the recent cinematic landscape, a resurgence in the popularity of psychological crime thrillers written by women (Gone Girl, The Girl on the Train). Many saw this as a breakthrough trend that women were finally getting recognition for writing successful suspense thrillers in a traditionally male dominated genre. However, this perception is problematic as it fails to recognise a legacy of female writers such as Patricia Highsmith, who set a precedent for noir writers many decades before for both women and men alike. Considered one of the first outstanding noir fiction writers in history, she is renowned for exploring the darkest and most complex depths of the human mind.

Her novels are invariably punctuated with elegant, methodical narratives of brutality, inner turmoil, murder, manipulation and dark humour. Strangers was her debut novel written in 1950, the first of many gripping, creatively violent novels which saw the same importance put on character as narrative. Her protagonists were habitually revealed to us as damaged, complex, clever, charming, self-destructive and deliciously obsessive; Highsmith was an expert (fictional) killer also adept at dissecting the sociopathic, homicidal psyche, much to our entertainment. Her characters are somewhat strangely captivating as well as monstrous, as they reveal their inner demons in addition to their cold sociopathy. Her other successful novel to film adaptations are most notably The Talented Mr Ripley books (aka The ‘Ripliad’) and The Price of Salt (adapted as Carol by Todd Haynes) which was revered for being the first lesbian novel with a happy ending.

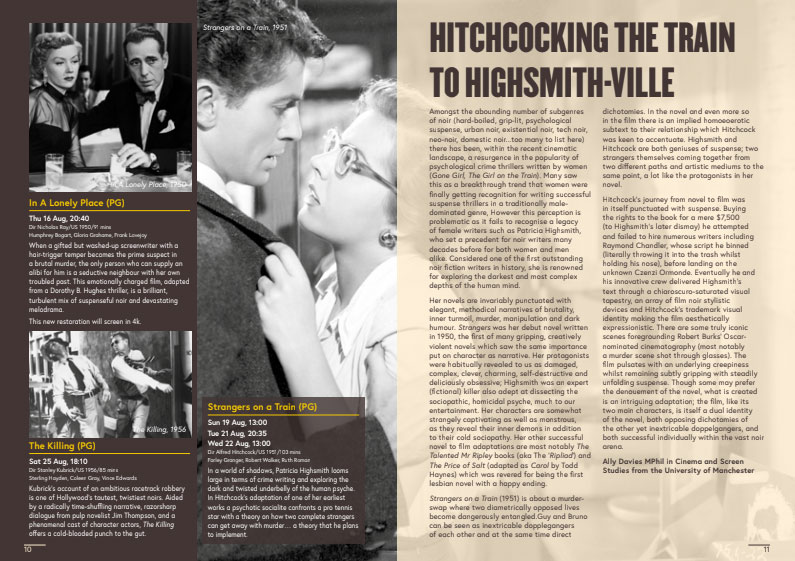

Strangers on a Train (1951) is about a murder swap where two diametrically opposed lives become dangerously entangled. Guy and Bruno can be seen as inextricable dopplegangers of each other and at the same time direct dichotomies. In the novel and even more so in the film there is an implied homoerotic subtext to their relationship which Hitchcock was keen to accentuate. Highsmith and Hitchcock are both geniuses of suspense; two strangers themselves coming together from two different paths and artistic mediums to the same point, a lot like the protagonists in her novel.

Hitchcock’s journey from novel to film was in itself punctuated with suspense. Buying the rights to the book for a mere $7,500 (to Highsmith’s later dismay) he attempted and failed to hire numerous writers including Raymond Chandler, whose script he binned (literally throwing it into the trash whilst holding his nose), before landing on the unknown Czenzi Ormonde. Eventually he and his innovative crew delivered Highsmith’s text through a chiaroscuro-saturated visual tapestry, an array of film noir stylistic devices and Hitchcock’s trademark visual identity making the film aesthetically expressionistic. There are some truly iconic scenes foregrounding Robert Burks’ Oscar-nominated cinematography (most notably a murder scene shot through glasses). The film pulsates with an underlying creepiness whilst remaining subtly gripping with steadily unfolding suspense. Though some may prefer the denouement of the novel, what is created is an intriguing adaptation; the film, like its two main characters, is itself a dual identity of the novel, both opposing dichotomies of the other yet inextricable doppelgangers, and both successful individually within the vast noir arena.

Words by Ally Davies MPhil in Cinema and Screen Studies from the University of Manchester. Article originally published in HOME’s film season brochure and on HOME’s website here.

Picture: ‘Supplied by HOME’

Copyright © 2019 Aesthetic Realms.

Website by Subzero.