Skeletons, re-animated patchwork dolls, giant unfurling hill organisms, sack-creatures filled with insects, undead corpse children with their eyes sewn shut and carnivorous door reefs. Not at first glance all the hallmarks of a Christmas family classic, however, The Nightmare Before Christmas, released in 1993, is still adored worldwide. It is no doubt an unusual Christmas film; the Christmas genre itself often over-stretched and teaming with over-sentimentality and excessive use of generic conventions. A question many have asked since its inception is; is it a Christmas film or a Halloween film? One could see it instead as a celebration of both. For it was born from Burton’s love of both holidays, observing isles full of Christmas and Halloween decorations piled side by side in local shops. And if we think of some of the most illustrious Christmas narratives, for example, Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, in all of its enduring permutations, one can see that Christmas and the ‘macabre’ have always been inextricably linked.

Nightmare is a demonstration of patience technically and an exercise in self-exploration and identity thematically. It is an examination of what we find to be the most basic human emotions; the search for something beyond the monotony of our repetitive lives; attempting to fill the holes we feel in ourselves; and our longing for something new and different. It is about the longing we have to be someone else and our desire for change. Furthermore, Nightmare is wholly immersive; within the first few minutes we are completely sutured into the very fabric of the narrative and the estranging world of its protagonists. We are led into a realm unlike any we have ever seen before, completely believing in it; it is poetry realised in the most tactile of visual techniques used for the screen. It is regarded as a masterpiece of skill and endurance as well as a film with heart, soul and genuine emotion. The genius of Nightmare comes from its perfect balance of poignant content and exquisite form. It also comes from the simultaneous occurrence of the macabre and comedy, of horror and love, of melancholy and redemption and of the weird and the endearingly beautiful.

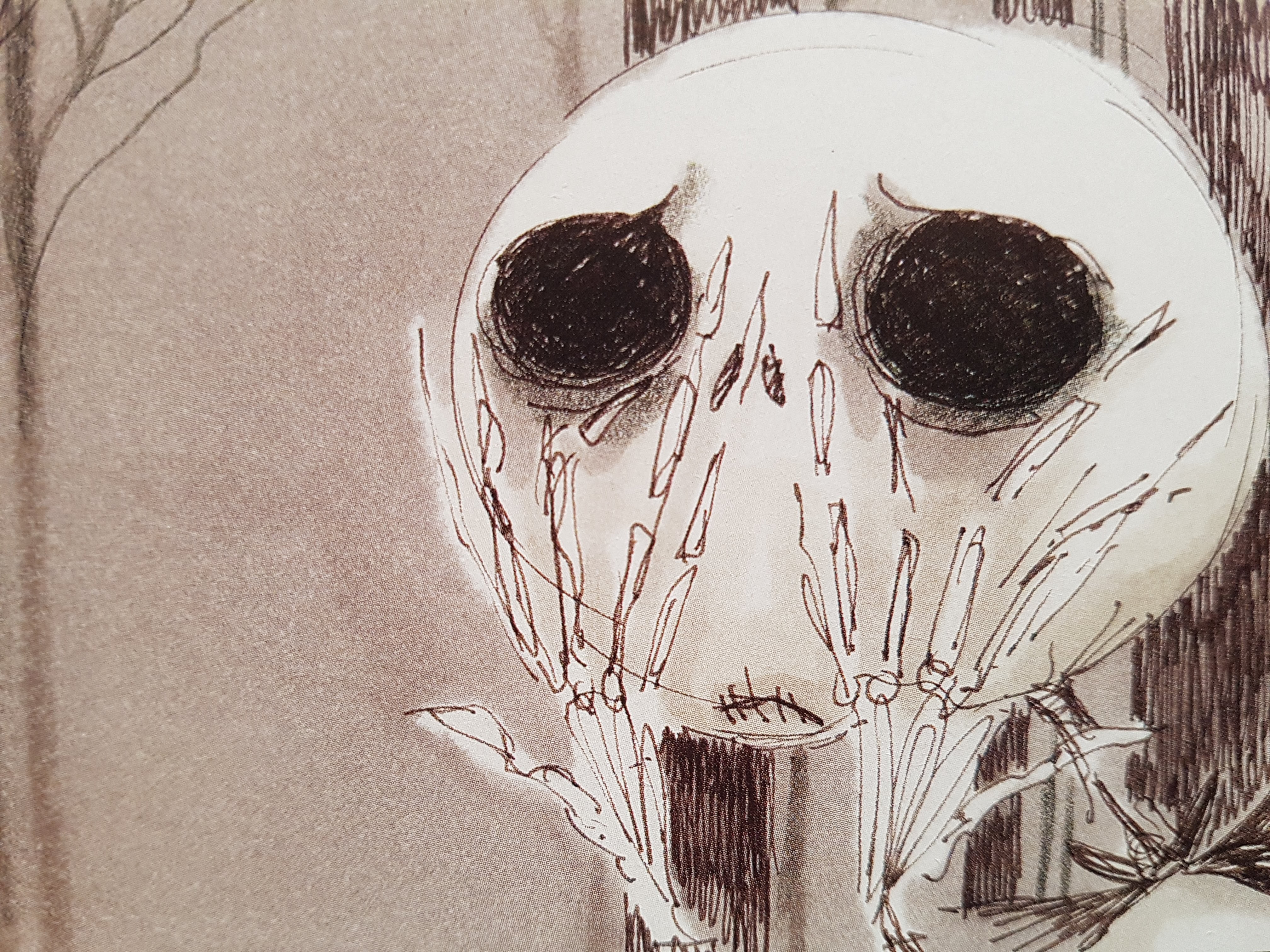

Let me begin by noting that a common misunderstanding of Nightmare is that it was directed by Tim Burton. Burton was indeed the original creator of the concept drawings, idea and poem, however, it was Henry Selick, a long-time friend and fellow animator of Burton’s from Disney in the 1980s, who Burton entrusted to direct the film. The film was first conceived in a Dr. Seuss stylistically-inspired poem Burton wrote with accompanying drawings during Burton’s internship at Disney in the 1970s. Both Burton and Selick felt dejected and trapped by the studio’s boundaries having to animate ‘cutesie’ foxes daily but continuously having their own more unique ideas shelved. Nightmare grew out of the frustration of this era but, born from boredom, came Burton’s signature dark, twisted themes and aesthetic that made him an auteur. He created strange worlds about a disillusioned Skeleton King having a mid-death crisis, looking for escapism from his monotonous existence. One can see the semi-autobiographical links to Burton here already. Jack stumbles across and falls in love with Christmas wanting to take it over to spread the joy himself. However, trouble inevitably ensues as the holiday beings’ worlds collide.

Disney, owning the rights and not wanting to touch it for being too bizarre eventually green-lit it for production on account of its tremendous emotive quality and originality. The process of getting Nightmare from concept to screen was equally as unique as the content of the piece.

Burton had always envisioned the film to be stop-motion animation and luckily Selick was regarded as a master of stop-motion and an industry maverick. He was familiar with this extremely time-consuming, complicated film technique. Stop-motion had been extremely popular featured in small increments in films but rarely had people attempted full-length features. Burton produced Nightmare which is why his name confusingly features above the title of the film, a marketing strategy by Disney due to him having claimed recent success with Batman (1989) and Edward Scissorhands (1990). Burton gave Selick complete creative freedom to bring his world alive and to use his own vision as they were creatively on the same wavelength. Part of his job was ‘to make it look like Burton’s hand was everywhere’ (Burton Film book). It’s important to know that when you are watching Nightmare you are watching a complete creative collaboration and shared vision, not only between Selick and Burton but including Christine Thompson, the final screenwriter, and the composer Danny Elfman. Selick took Burton’s poems and drawings and with his team expanded on the world of Nightmare. In fact, Burton was rumoured to have only visited the set of Nightmare in San Francisco a couple of times during the three year production process.

Stop-motion itself has a longer history than one would expect from such a multifaceted technique. The first instance of stop-motion was in Albert E. Smith’s and J. Stuart Blackton’s The Humpty Dumpty Circus in 1897. They described it as a wearisome process and failed to obtain a patent because they never thought it would ever become important enough. It was later used by a number of renowned practitioners from George Melieres and Landislas Starevich to Ray Harryhausen and crept into some of the most acclaimed films in cinema history such as King Kong (1933), Jason and the Argonauts (1963) and Clash of the Titans (1981). It later came into its own in screen favourites like Star Wars (1977), Robocop (1987) The Terminator (1984), The California Raisins (1986) and the multi award-winning Aardman Animations in the UK with Creature Comforts (1989) and Wallace and Gromit (1989). Nightmare was the highest grossing stop-motion animated film of its era. For some, however, it still feels like an underrated art form. It has a tactility and a physicality unrivalled by other mediums; it gives its characters a solidity and a material, corporeal presence.

With production housed in San Francisco, the hotbed of stop-motion and special effects, author Frank Thompson notes in his book Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas (2009), ‘at the time it was the most elaborate, ambitious, complex stop-motion animation film ever made….he began building a giant stop-motion crew from the ground up. It was great opportunity to bring together the best mould makers, sculptors, armature makers, fabricators, set builders, camera people, computer people and animators from around the world; it was a very rare approach to animation.’ Paul Berry, a Cosgrave artist working on Nightmare, had also said that he had never worked in this way before; it was a completely different approach to anything he’d ever worked on. Not only did they spend forever getting each shot to look perfect compositionally, on an acting level as well, ‘the amount of energy poured into each shot was unusual’ (Frank Thompson, 2009).

The aesthetic to Nightmare can be described as deeply ‘Burtonesuqe’, a term coined to encapsulate his own distinguishing stylistic traits. Burton is an auteur; he has a defining and specific vision that can be found through most of his films, in my opinion, even more so in his earlier work where his signature was strongest. Dark, twisted, deeply metaphorical emotive qualities are captured within his mise-en-scene, music, production design, costumes, cinematography, characters and themes, all working together to create his trademark twist of unusual, distorted, distinctive beauty. Thematically, his films usually feature some kind of misunderstood character; an outcast individual experiencing otherness or alienation. His characters are the embodiment of recurring themes that echo throughout his work. This consistency of stylistic devices is carried on into Nightmare’s aesthetics and themes which are laden with intertextual signifiers across all of his projects. He has a methodology and a particular iconography with vital components. For example, use of body modification art, being pierced or stitched, bondage wear, buckles, stripes, varieties of clothing textures such as laces and netting, alternative punk culture fashion, strange angular architecture and interior designs, exaggerated design features, costumes and hair, skeletal trees, spirals, graveyards, skeletons and low-key/high contrast lighting. This unconventional self-imaging made him a brand name amongst many alternative subcultures (including goths, punks, moshers, grunge groups, steampunk groups, emos, nu-metal rockers) within society in the 1980s and 1990s that too found solace and kinship in embracing the different and rejecting ideas of conformity.

Burton spent his childhood as an outsider creating anti-societal views and rejecting the status quo and what was deemed ‘social normality’. He believed that social ‘norms’ should be challenged and questioned and he wanted to assert alternate ways of livings. He grew up introspective with an adoration of horror films and the morbid and inspired by Edgar Allan Poe and Roald Dahl imagery and symbolism. His alienated youth gave him the thematic propulsion for his visions. Concepts set in small-town dystopias, exploring estrangement, naivety, morality, social breakdowns, self-acceptance, bullying, death, conformity and examining our humanity. His aesthetic translates directly into feelings and has the power to jump from the screen with a tactile, visceral, penetrative, haunting quality.

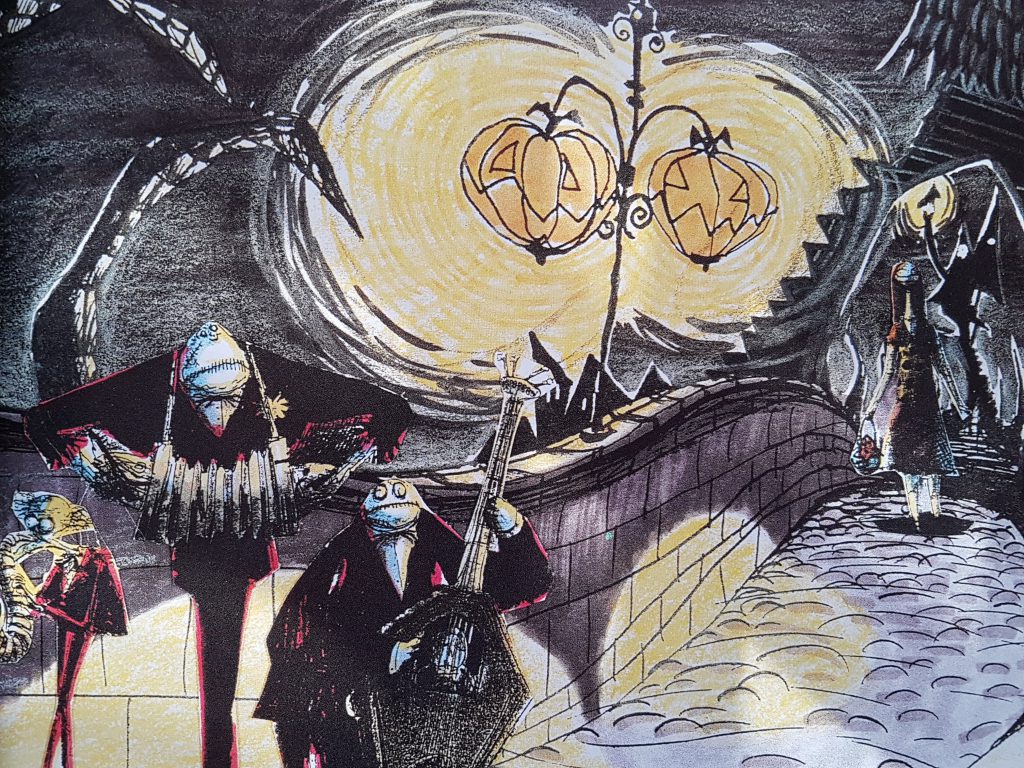

Nightmare has a visual richness that was inspired by a number of influences. Indeed within Nightmare’s aesthetic (and most of Burton’s and Selick’s work) one can see a German Expressionist influence. German Expressionism was a creative movement that met its height in the 1920s, some notable films of this genre being The Cabinet of Dr Caligari (1920) and Nosferatu (1922). A key component of German Expressionism was distorting the world radically for emotional effect thereby evoking intense moods, feelings or ideas. Stylistically it uses low-key high/contrast lighting and lighting with use of heavy shadows which represented psychological reality and heightened the sense of alienation or ‘otherness’. This lighting effect is also known as the Chiaroscuro effect, an oil painting technique developed in the Renaissance that uses strong tonal contrasts between light and dark to dramatic effect (later being applied to photography and cinematography). German Expressionism conveys the inner emotions of its characters and the zeitgeist of a particular era through the careful consideration of stylistic techniques; the fictional world is warped as a reflection of the artist’s intended emotional state. The use of heavy shadowing along with theatrical actor movement are practiced in German Expressionism to suggest a warped or perverted perspective of the world; Nightmare’s production design emphasises the distorted reality that Jack feels and his inner emotions.

In Halloween Town the architecture is angular with distorted shapes and lines reflecting the way Burton felt as an outcast and the way society views the strange and different. However, the characters in the film may live in a world of perpetual horror and ‘nightmarishness’ but that is their comfort and normality. In Nightmare one can contend that this design is not meant to reflect their perversion but just their ‘otherness’ and their unique perspectives on the world. They are simply different beings with different purposes that are valid within the mythology of their own universe within the diegesis of the film; all the holidays have their place and our world needs them all, whatever form they come in.

Selick wanted Halloween and Christmas Town to be two very distinctive worlds and production designs; they were to be environmental, architectural and atmospheric dichotomies. Christmas Town is soft, bright, fluffy, rounded, colourful and full of Christmas iconography textures and patterns. Halloween Town is angular, off-edge, off-balance and overcast using greys, blacks and muted oranges. As Selick described ‘Halloween Town was to be something if you ran your hand over it, it would cut you’ (Frank Thompson, 2009). He wanted strange perspectives, so much so that if the artist could not quite get the right look of a piece some of the right-handed artists began drawing with their left hands, and vice versa, which would make their work slightly more off-kilter and unsound. Burton too, often did this. Within Nightmare’s aesthetic depths can also be seen very sketchy-line work where set pieces and characters clothing contain deeply etched textures and cross-hatching which was inspired by artists Edward Gorey and Ronald Searle. Selick’s artists would smear clay onto the objects and scratch into them to give them the ‘living sketch’ look.

The visual tapestry in Nightmare is immense thanks to the painstaking work of the artists. What astounds every time we watch it is that most of what you see in the film has actually been built (bar a few minor moments of cell animation). Every rock, branch, building, gate, carpet, wallpaper, utensil, twig, pavestone and character has been constructed. Seeing it on the big screen is a whole new experience even if you have seen it hundreds of times before. One is continuously blown away by the extra detail missed on the small screen; I myself only saw it on the big screen during its 3D re-release in 2006 and was amazed that I had never noticed that Zero’s nose was not only a Rudolph glowing nose but a jack o’ lantern with a face). Thousands of props were made along with 227 puppets; Jack alone had 400 heads. One minute of footage took a week to shoot and even the way it was shot had more in common stylistically with the cinematography of a live-action musical with sweeping, elegant tracking and crane shots.

Another key component to Nightmare, and indeed to Burtons other films, is the emotional depth, intricacy and passion of his protagonists, Jack Skellington being a noteworthy example. Jack follows closely the classic tragic hero archetype and suffers an existential crisis, haunted and consumed by a deep longing for something better. Jack’s journey is the search for identity and self-acceptance; even though he is top of his game as King of Halloween he is melancholic. He is angst-ridden and tormented by disconnection and seclusion. He desperately wants to feel something but numbness and is looking for something new. These can be read as autobiographical inferences as Burton’s own escape fantasies from the monotony of his hometown and Disney. It is a common thought amongst us all to want to try new things or be in someone else’s shoes for a day. Jack is light and dark, scary and gentle, kind but also a genius of terror but he wants to be more than just scary. Disney were adamant that Jack was given eyeballs as a crucial element to connecting with an animated character was the expressive eyes, however, later it was proved that Jack did not need eyes for an audience to emote to him as deeply as they do. He may have no skin, no muscles and no eyes but Jack still has huge depths.

Most significant of Burton’s self-created archetypes is the ‘misunderstood outcast’, a character that tries to do good but somewhere along the line it all fails. Jack fits this as he is the embodiment of hope and naivety but he is uncompromising, self-absorbed and obsessive. He hijacks Christmas not from any malicious intent but from a burgeoning love for this new found holiday and the feeling it gives him; he essentially falls in love with Christmas and is fascinated by it. This feeling he finds in Christmas Town fills the holes of loneliness within him and he doesn’t think logically about the pitfalls of this idea and instead is only led by his misguided emotions. He unintentionally drives both Christmas Town and the real world into sheer panic and fear but what is sad, funny and poignant is that he only intended to spread joy and try to fill a hole in his heart. His true strength of character is seen in his desire to correct his faults and to help those he has unknowingly wronged.

There was nothing typical about the process of this masterpiece, none the least in the creation of its unique score; a divergent approach to scoring a Hollywood film was used. Usually a script to a musical would be written first and the composer would later find a way to add in the songs but Burton and Elfman developed the music before the script was written. They began with the basic outline of the narrative and Elfman helped develop personalities, atmospheres and tones by writing the songs. In this way the narrative and music evolved together, as Frank Thompson explains, ‘Burton’s story ideas triggered responses in Elfman who wrote the songs, the songs in turn suggested new story points for [Caroline] Thompson whose revisions of the script left Burton to alter and expand the original story.’ Funnily enough, every element of the production began before there was a final script. Like a loveable monster in Halloween Town the script was an ever evolving, living breathing entity, gaining momentum as every team member became more consumed and inspired by the project.

It took two decades from concept to release to bring this groundbreaking project to life. It is indeed a beautifully executed collaboration very much Selick’s vision with the mark of Burton. It catapulted stop-motion to the next level drawing us into every frame of the screen and filling us with a richness of off-beat, subversive energy. Nightmare explores the idea that finding oneself is a lifelong task. Perhaps the answer isn’t just finding oneself once but perhaps one finds oneself over and over again throughout one’s life. It’s ok to become bored with routine, we can try new things and we can enjoy them but we always come back to what essentially makes us, us. There is something comforting and reassuring in this notion. We are who we are and we should embrace that. These heartwarming ideals are embedded within every Christmas film so perhaps Nightmare, despite the skeletons and monsters, is a film that holds the true meaning of Christmas.

Nightmare’s production techniques and cinematography allow us to actually engage with the world being presented; the use of stop-motion allows us to cross a boundary; characters are animated so well in terms of actors’ physicality and movement that a deeper reality to these creatures is created and we feel we can reach out and touch them; and three-dimensional character arcs make us feel that they go on beyond the world of the diegesis being presented.

Nightmare is a film that inspired a new generation of artists; it inspired tattoos, fashion trends and even weddings (not mine of course but a friend’s). It still provides a truly haunting filmic experience. It is something we have grown up and evolved with, like a childhood friend. The next time you watch it make sure to have a look at each and every corner of the frame to see all the visual surprises packed into every nook and cranny. The world of Nightmare is not only a love affair with the delightfully macabre and the transformative nature of experience but a love affair with the incredible craft of stop-motion animation. As Burton said himself ‘Nightmare is deeper in my heart than any other film. It is more beautiful than I imagined it would be. As I watch it, I know I will never have this feeling again, The Nightmare Before Christmas is special’ (Frank Thompson, 2009).

Ally Davies is the director of Aesthetic Realms and has worked in the creative arts industry in a variety of roles. Her academic career includes gaining a BA, MA and MPhil in Cinema and Screen Studies from the University of Manchester as well as attending Art School. Her MPhil specialist research area covered post-9/11 American politics and the audiovisual aesthetics and design in film and television space-based science fiction. She also likes pumpkins. A lot.

Ally Davies is the director of Aesthetic Realms and has worked in the creative arts industry in a variety of roles. Her academic career includes gaining a BA, MA and MPhil in Cinema and Screen Studies from the University of Manchester as well as attending Art School. Her MPhil specialist research area covered post-9/11 American politics and the audiovisual aesthetics and design in film and television space-based science fiction. She also likes pumpkins. A lot.

Copyright © 2019 Aesthetic Realms.

Website by Subzero.